India recently agreed to opt-out of a trade agreement with the 16-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). India concluded that before “significant outstanding issues” are addressed, it would not become part of the RCEP. The RCEP negotiations were initiated during the 21st ASEAN Summit in Cambodia, November 2012. All participating countries tried to finalize and sign an agreement by 2020.

What is RCEP?

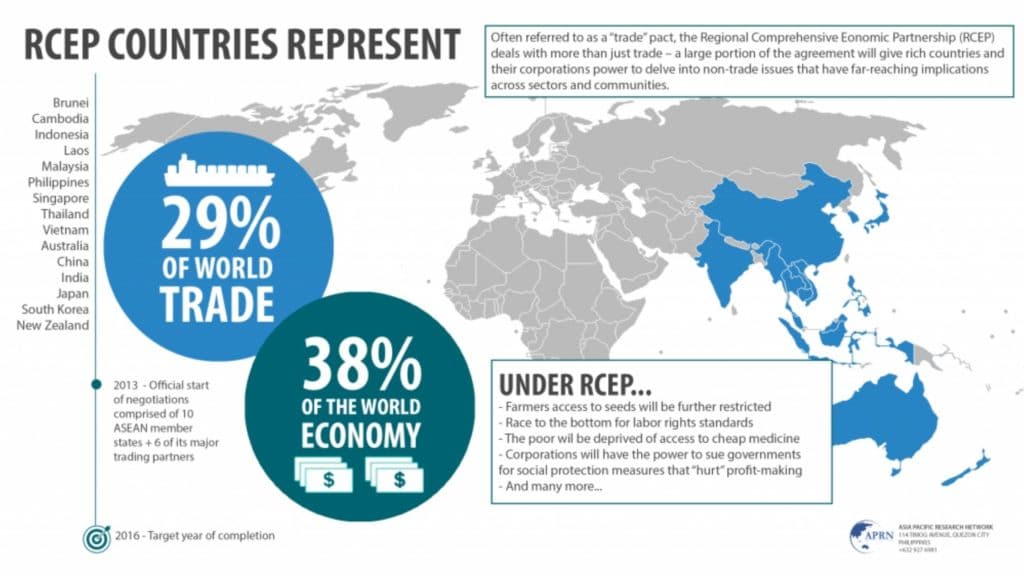

An agreement to expand and deepen ASEAN’s participation with Australia, China, Japan, Korea and New Zealand is the (RCEP) agreement. Together, these participating RCEP countries account for nearly 30% of global GDP and 30% of the world’s population. The RCEP agreement aims to establish a new, inclusive, high-quality and mutually beneficial economic partnership. It will create business and job opportunities for companies and individuals in the region. A transparent, inclusive, and rules-based multilateral trading mechanism will operate alongside and endorse the RCEP Agreement.

RCEP is a trade deal which was in negotiations among 16 countries.

They include the ten Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) members (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam). The six nations with FTAs are India, China, Korea, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.

Key features of RCEP

- Modern

- Compressive

- High quality

- Mutual beneficial

Reasons for India’s Withdrawal

Unfavorable Balance of Trade

While trade with South Korea, ASEAN countries and Japan has increased since the FTA, imports have increased more rapidly than India’s exports.

India has a bilateral commerce deficit with most of the RCEP member countries, according to a paper released by NITI Aayog.

Dumping of Chinese Goods

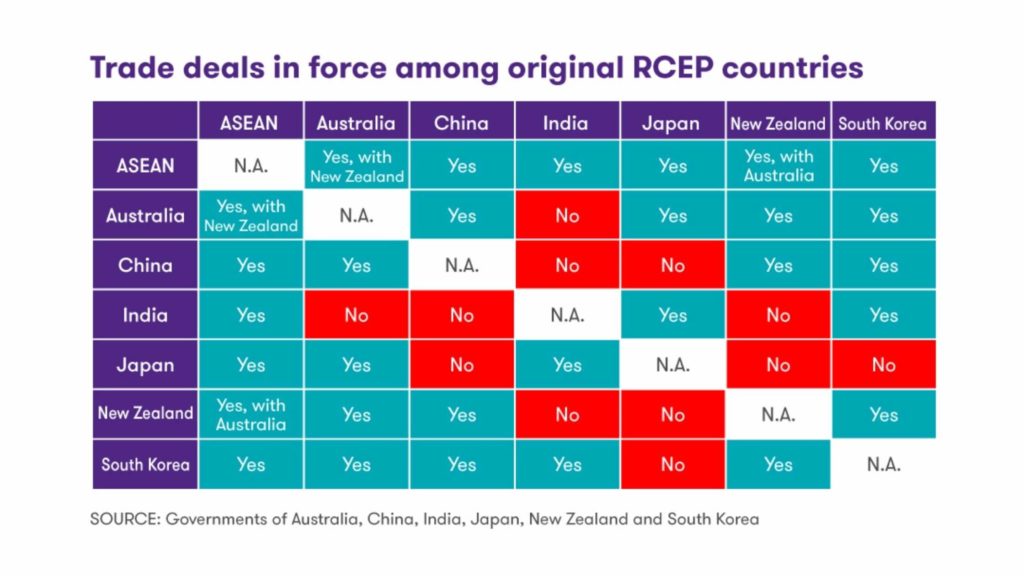

In addition to China, India has already signed FTAs with all the RCEP countries.

This is India’s primary concern, as China’s cheaper goods would have entered the Indian market after signing RCEP.

Non-acceptance of Auto-trigger Mechanism

India had sought an auto-trigger mechanism to deal with the imminent increase in imports. The auto-trigger tool would have allowed India to raise tariffs on goods when implications reach a certain threshold. However, many countries are opposing this proposal in the RCEP.

Protection of Domestic Industry

India has also reportedly raised concerns about reducing and removing tariffs on certain goods such as dairy, steel, etc. For example, Australia and New Zealand are likely to face tough competition from the dairy industry. Currently, India’s overall bound tariff for dairy products is 35 per cent on average. The RCEP obliges countries to reduce the current level of taxes to zero within the current level.

Lack of consent on Rules of Origin.

The parameters used for determining the national source of a commodity are the rules of origin. Present clauses in the agreement allegedly do not prohibit countries from routing goods. India can retain higher tariffs through other countries. India was concerned about “possible circumvention” of the origin rules.

Implications of India’s Exit from RCEP

India can still maintain a track on China’s dumping of products in India if it exits RCEP. Nevertheless, from needles to the turbine, Chinese items are all over the Indian market. Refraining from the RCEP will shield the Indian domestic industry from cheap imports. The RCEP is a China-backed trade agreement and will further boost China’s economic power by signing it without India.

As China is already trying to influence the region through its deep pockets, it will affect India’s neighbourhood. India plans to become a manufacturing hub. However, staying out of RCEP limits trading prospects with these nations, which together accounts for approximately one-third of global trade. Today’s manufacturing requires greater convergence with global supply chains. The signing of the agreement would have signalled the introduction of freer trade, which could have helped move businesses from China to India.

2/3 India’s withdrawal from the RCEP could also affect India’s East Policy Act. India could have benefited from this as an opportunity to drive through divisive yet required competitiveness-boosting reforms.

Why India opted out?

We also saw news of what Prime Minister Modi had communicated to the Bangkok Summit2. It allegedly claimed that the outcome of the RCEP did not wholly represent the fundamental spirit. The guiding principles, initially agreed to negotiate the RCEP; it called, among other things, for a substantive and fair outcome and for the RCEP to contribute to the sustainable economic growth of the participating countries.

To offer more significant equity and balance, India has put forward some clear proposals for consideration. And these were not satisfactorily handled. The Prime Minister further claimed that he did not get a positive response when he assessed the agreement about the needs of all Indians.

As sources suggested or were they around for a while, did India raise some issues at the end?

For someone not privy to the talks, this is once again a tough question to address. However, most of the particular amendments sought by India that the Home Minister referred to in his post. For instance, the need for a well-designed safeguard mechanism against import surges has been a priority to India. There is no intellection to believe that they might not have been expressed earlier.

India’s decision was the economic downturn and a gloomy mood within the country that had seen exports stagnate, among other items. During the weeks leading to the RCEP summit, there was increased domestic opposition to RCEP from many industry and farming sectors. Although RCEP received no mention in the 2019 election manifestos, opposition voices arguing against it became louder in the nearer summit, politically too.

The Five Most Influential Demands in India

The five most prominent requirements mentioned explicitly in the Home Minister’s article may not have meant changes in the tariff differential. India has requested greater flexibility from the outset on tariff reduction about China and those other RCEP countries with whom (Australia and New Zealand) Industry has asked for it (FTA). It would automatically have implied a disparity to the cumulative provisions in the rules of origin for these nations since to be meaningful; the two must be in harmony.

It may also be problematic to grant MFN requirements and ratchet obligations in trade in services if unqualified. The MFN clause means that any concession given to any third country, including some of India’s neighbours, will have to be granted immediately to the members of the RCEP. Similarly, ratchet duty suggests that India’s autonomous liberalization is at least locked in for RCEP members. Such a commitment is challenging for a developing country like India and may even restrict autonomous liberalization.

Also, such clauses have not been found too much in Asian FTAs. One study cited that seven of the eight FTAs it analysed in China do not have MFN provision. Where it was there, there are sectoral exemptions in the China-New Zealand FTA. For example, China restricted its MFN duty in this FTA to the similar treatment given to other countries of the OECD for services incidental to agriculture and forestry. Moreover, the study noted that various FTAs with MFN provisions eligible them by clauses 8, restricting their extension or enabling exemptions.

Accordingly, India’s solution in the RCEP would have been to list its non-conforming steps and take the exemptions deemed appropriate. However, more can be said here only after understanding what exemptions and non-conforming measures India would have wanted to register and what, if any, other members may have objected.

This is due to a significant change in our interim tariff rate for pursuing tariff reduction adjustment in the base year to 2019 versus 2014. And this is where one could read the Secretary’s (East) comment on the changed international situation that has prompted some countries, worried about increasing imports of products with surplus capacity in some countries, to defend themselves by raising tariffs.

Some of the electronics imports have skyrocketed as far as India itself, which has prompted us to put tariffs on them. The government did not want such amendments to weaken by agreeing to the RCEP.

A Difficult Negotiation for India was admittedly RCEP.

It does appear India negotiated hard from all indications. Considering the number of countries involved, the variety of issues covered, and the China factor, the RCEP negotiations were among India’s most challenging trade negotiations.

In the negotiation room, the Indian negotiator would also have been the most unenviable individual because all other participants were representatives. Except for perhaps Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar (CLM), were much more acquainted with each other personally and with their business practises and policies, being part of APEC. All these countries are pacing towards exports.

They have also been part of numerous APEC programmes and action plans implemented over the past two decades. Simultaneously, peer pressure among them, coupled with the competition, has dramatically improved their logistic and trade facilitation indices. Even if India prepares to accelerate reform steps in these regions, the close calculation would have taken some time.

Should India be approached for Reconsidering RCEP?

Finally, should India, sooner or later, be approached again to join the RCEP? What could be the guiding elements in our consideration? As this writer is not aware of the specifics of the finalised text of the RCEP or the particular amendments proposed by India to that text, the response can only be general.

First and foremost, India should not merely force to take some good regional hits. Still, other members of the RCEP need to demonstrate some accommodation for the production of win-win solutions. Suppose we soon follow an action plan to double exports over the next five years. What should be a key benchmark for India is whether the text of the RCEP with the amendments that may be agreed will substantially boost our chances of achieving this doubling of the target.

Secondly, some differential and cumulative tariff delays and a longer tariff reduction timeline of up to 15 to 20 years would be necessary for non-FTA partners. India can agree to bring domestic tariff increases to previous levels in recent years within a short period.

Thirdly, it would be essential to have a properly planned safeguard system specifically for farm products, industrial products with surplus ability in the area and other things.

Fourthly, the services sector’s balance can be seen as balancing inevitable potential trade-offs with possible losses on the goods side.

In earlier FTAs, such a strategy did not secure real benefits on the service side, likely also tilting the scale against us on the product side. Many other RCEP countries are reasonably high in several services sectors under Mode 3 (commercial presence). Mode 1 (cross-border trade) and available statistics also show that, unlike the United States, India has no trade surplus with countries in that region on services.

This brief sought to situate and understand India’s decision not to join the RCEP, especially amid the imperatives of some looming international trade challenges. Whether or not India is in the RCEP, this brief attaches significance to India’s rapid action on:

The creation and implementation of a double export action plan over the next five years can be written as:

- The development of an FTA strategy.

- The advancement and implementation of a productive and robust import regulation framework.

In the meantime, if the other RCEP members decide to be more accommodative to India and its requirements. And show their willingness to negotiate a win-win agreement for India, this should be welcomed. However, the decision to join should mainly be judged based on whether it will substantially lead to India’s doubling of exports over the next five years.

It is also essential to bear in mind whether we can keep our imports within manageable limits. Whether RCEP implementation can be incorporated into our domestic reform process, our negotiators will need to develop innovative ideas for all this, for which business wants to offer a helping hand.

Follow us on FACEBOOK, INSTAGRAM and TWITTER to stay connected.

Also Read- India’s Challenges over Carbon Footprints