It is a horrible global allegation that, after decades of sustained success in reducing global poverty, climate change and war, food security in the world’s most vulnerable countries is now threatened. We can no longer afford to treat the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Climate Agreement as voluntary and a matter for each Member State to determine its own. The number of hungry people increasing from 785 million in 2015 to 822 million in 2018. Instead, to establish a vibrant community for our children and grandchildren, the complete implementation of both has become imperative.

On the global political stage, this needs a change of mind-set. While we live in a period of great confusion, a greater consensus is beginning to emerge about the need for change. We must consider the inextricable links between environmental, sustainability and social justice when we see the simultaneous and compounding effects of climate change, inequality, violence, poverty or hunger. This awareness provides possibilities and impacts on a never-ending scale for galvanized action. These activists of today are the next generation.

The next generation includes children whose health and wellbeing are influenced by undernutrition and whose future is determined by our actions in the field of climate change—or inaction. We’ve just got a decade left. While a fundamental ambition of the Sustainable Development Goals is the pledge to achieve Zero Hunger by 2030, our hard-won gains are under pressure now or are being reversed. Global hunger had transitions from extreme to moderate.

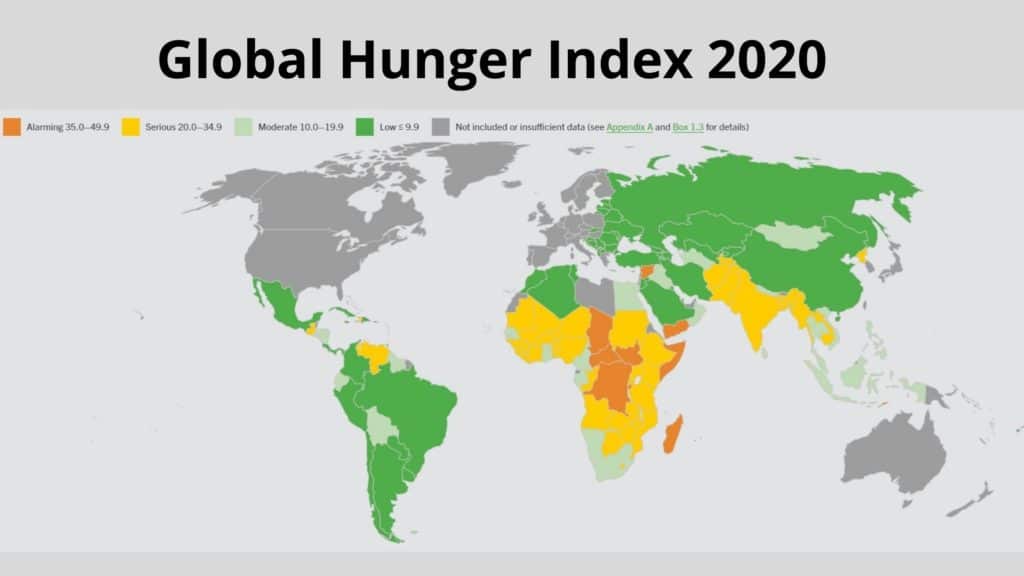

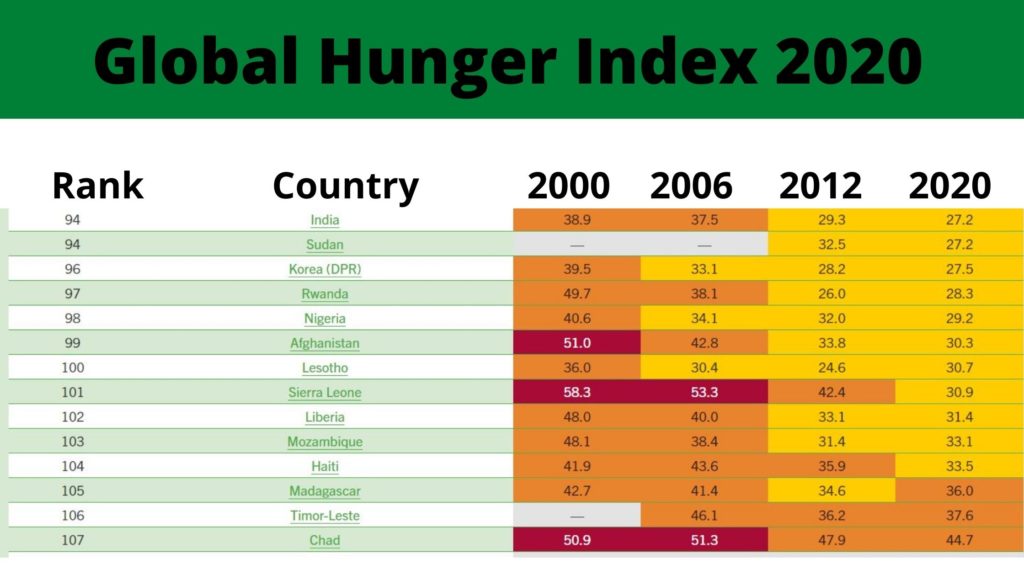

In several parts of the world, extreme weather disasters, violent conflicts, wars, and economic slow-downs and crises continue to spur hunger. The number of undernourished individuals increased from 785 million in 2015 to 822 million in 2018. In the mild, severe, worrying, or highly alarming groups, nine GHI countries have higher scores today than in 2010, including the Central African Republic, Madagascar and Yemen. And in this article, we will concentrate on why Yemen and central African republic are falling apart severely?

Concept of Global Hunger Index

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is an instrument designed to quantify and monitor hunger at global, regional and national levels systematically. Each year, GHI scores are measured to test and reverse the battle against hunger. The GHI aims to increase awareness and understanding of the fight against hunger and compare hunger levels between countries and regions and draw attention to those parts of the world where hunger levels are highest and a greater need for additional efforts to eradicate hunger.

It is challenging to quantify starvation. It helps to understand how the GHI scores are measured and what they can and cannot tell us to use the GHI data more efficiently. According to the 2019 GHI, four countries for which information is available to suffer from alarming hunger levels, and one nation, the Central African Republic, suffers from disturbing stories. Chad, Madagascar, Yemen, and Zambia are the four countries that have problematic hunger levels. Of the 117 countries that have been ranked, forty-three countries have significant levels of hunger.

According to the 2019 GHI, the Central African Republic suffers from an extremely alarming hunger level from the countries for which data is available, while four others, Chad, Madagascar, Yemen, and Zambia, suffer from alarming levels of hunger. 43 of the 117 countries that have been ranked have extreme levels of hunger. The GHI study also looks more closely at hunger in Haiti and Niger, both of which are extremely vulnerable to the impact of climate change and have extreme levels of hunger.

What is hunger?

It is widely understood that hunger refers to the discomfort associated with a lack of enough calories. Food deficiency or undernourishment is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as the consumption of too few calories to provide the minimum amount of dietary energy that each needs to live a safe and productive life given the sex, age, stature and physical activity of that person.

The level of hunger and undernutrition worldwide is on the apex of the mild and extreme categories with a 2019 GHI score of 20.0. This score represents a 31 per cent decrease since 2000 when the GHI global score was 29.0 and fell into the extreme category. This progress is focused on declines in each of the four GHI indicators since 2000, such as undernourishment rates, child stunting, child wasting, and child mortality.

What causes hunger?

- Poverty

- Food shortages

- War and conflict

- Climate change

- Poor nutrition

- Poor public policy

- Economy

- Food waste

- Gender inequality

- Forced migration

The Central African Republic

In the Central African Republic (CAR), a landlocked country of approximately 4.8 million people, violence has disrupted livelihoods and food security since 2012. Insecurity continues to restrict humanitarian access to vulnerable populations, and economic and agricultural activities continue to be limited.

According to the UN, there were more than 697,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in CAR and almost 616,000 Central African refugees seeking shelter in neighbouring countries. Between December and March, worsening conflict and insecurity, especially in northeastern CAR areas, displaced approximately 27,000 people and impeded humanitarian response efforts, leading to higher levels of food insecurity.

According to the most recent IPC report, nearly 2.4 million individuals are likely to face worse acute food insecurity levels from May to August. This period includes the lean season when food is scarcest, primarily due to growing conflict and displacement.

According to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network, an early start to the lean season in March and movement restrictions imposed to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) led to sharp rises in the price of critical food products across CAR in March and April, decreasing the ability of low households to buy food. Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET).

An estimated 1.3 million CAR people, including approximately 50,000 children under five years of age suffering from extreme acute malnutrition, will need assistance to prevent and manage malnutrition in 2020, the UN estimates.

“The Integrated Step Classification of Food Security (IPC) is a structured instrument that seeks to identify the severity and magnitude of food insecurity. The IPC scale ranges from Minimal-IPC 1-to Famine-IPC 5, which is comparable across countries.”

Humanitarian Response to this Crisis

The UN World Food Program (WFP) provides help to refugees, IDPs and host communities impacted by war and poverty with in-kind food and food vouchers with support from the USAID Office of Food for Peace (FFP). With the assistance of the FFP, the WFP is also conducting a supplementary feeding programme to prevent and manage malnutrition targeted at children and pregnant and lactating mothers.

FFP NGO partners support IDPs and host community members in the prefectures of Basse-Kotto, Haute-Kotto, Haut-Mbomou, Mbomou, and Ouaka ACTED, Concern Worldwide, Mercy Corps, and Oxfam Intermón by conducting food-for-assets activities and offering food vouchers, cash transfers, and locally generated food.

The FFP is also collaborating with ACTED, the Samaritan Purse and the WFP to provide emergency food assistance to refugees from Central Africa residing in Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo.

Total contributions (MT- metric tons)

The fiscal Year 2020- $31.9 million (13,299 MT)

The fiscal Year 2019- $50.8 million (18,000 MT)

The fiscal Year 2018. $36.2 million (15,962 MT)

Why does Africa have no food?

Hunger is rising at an unprecedented pace in Africa. Years of progress are reversing economic woes, famine, and severe weather so that 237 million sub-Saharan Africans are chronically malnourished, more than in any other country. Hunger is faced by 257 million people in Africa, which is 20 per cent of the population.

Successive crop failures and poor harvests take a toll on agricultural production in Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Angola, and food prices are soaring. Sections of Southern Africa have witnessed their lowest rainfall since 1981 over the past three increasing seasons. In March and April 2019, other areas experienced widespread damage from Cyclones Idai and Kenneth near the time for harvest.

These dire events have resulted in food insecurity for 41 million people in Southern Africa and immediate food assistance for 9 million people. As farmers and pastoralists struggle to make ends meet during the lean season from October 2019 through March 2020, the number is expected to grow to 12 million.

Estimated at 65 million people, Africa was home to more than half of the global number of acutely food-insecure individuals in 2018. At 28.6 million, East Africa had the highest number, followed by 23.3 million in Southern Africa, and 11.2 million in West Africa. Between October 2019 and January 2020, food security is declining and is projected to deteriorate in some countries.

YEMEN

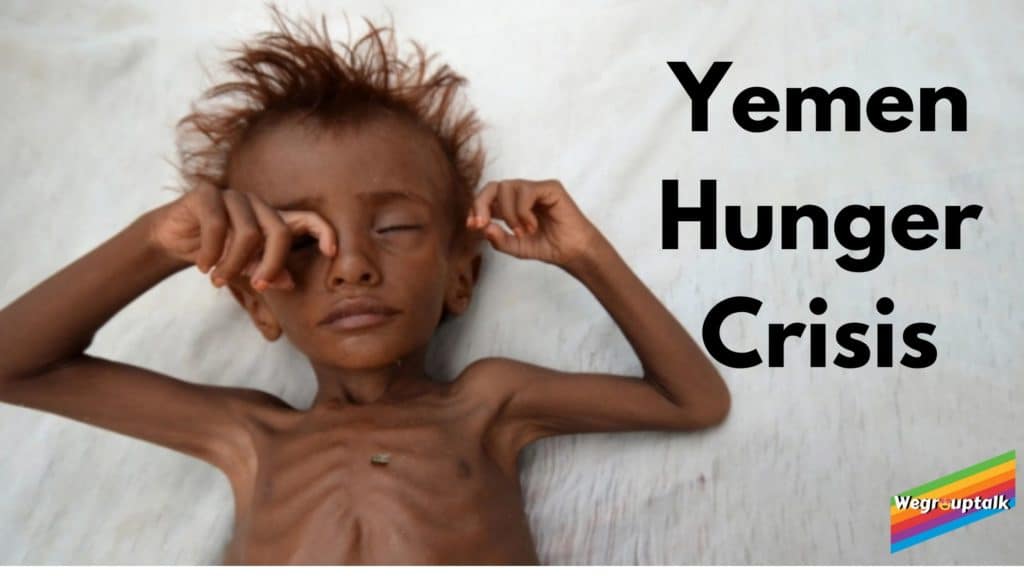

Yemen’s drought is unprecedented and is causing extreme misery for millions of people. Despite ongoing humanitarian assistance, more than 20 million Yemenis are food poor, almost 10 million of whom are food insecure. The proportion of child hunger in the world is one of the highest, and nutrition level continues to decline.

Nearly one-third of families have differences in their diets, and barely ever consume foods such as vegetables, pulses, fruit, meat or milk products, a survey found. The rate of malnutrition among women and children in Yemen remains among the world’s highest, with more than one million women and 2 million children needing care for acute malnutrition.

The hunger situation in Yemen is categorized as alarming. According to the new food security assessment published in December 2018, 20.2 million people (about 76 per cent of the total population) will face life-threatening food shortages without the assistance provided by the humanitarian community. This is almost twice Sweden’s population.

This involves people who or IDPs, have been internally displaced. Due mainly to the war, 3.34 million IDPs were displaced across 21 governorates (2019 Humanitarian Needs Overview). Taiz, Hajjah, Sana’a City, Sa’ada and Sana’a Governorates account for 85 per cent of the conflict-related IDPs.

Yemen is on brink of Starvation

“If we do not receive urgent funding, children will be pushed to the brink of starvation, and many will die. The international community will be sending a message that the lives of children in a nation devastated by conflict, disease and economic collapse, do not matter”, Ms Nyanti pointed.

Yemen five years on Youth, Conflict and COVID-19 warn that more than 23,000 children with extreme acute malnutrition will be at increased risk of dying unless US$54.5 million is raised for health and nutrition services by the end of August; there will be shortages of child immunization; and 19 million people will lose access to health care, including one million pregnant women and breastfed children.

Causes of Hunger in Yemen

Armed Disputes

The fundamental cause of food insecurity in Yemen is an armed war, which restricts people’s ability to access the food they need to survive. Nearly 65% of people facing catastrophic food gaps live in four provinces: Hajjah, Hudaydah, Sa’ada and Taizz. These regions have witnessed the most violent struggles in the past year, including air strikes, land battles and bombing. The United Nations is working to negotiate a peace agreement between the warring parties. The UN Secretary-General described the peace talks held in Sweden in December 2018 as a critical step towards achieving sustainable peace in Yemen.

Economic Meltdown

In Yemen, the war has precipitated an economic collapse that has worsened the food security crisis even further. Food prices have sky-rocketed, aggravated in the Riyal by decreased access and drastic fluctuations. Unemployment rates have also increased, making essential food for many Yemenis unaffordable. High food prices push people to follow detrimental coping strategies, such as moving to cheaper and less desired food or reducing their number of meals.

Due to decreased local food production, dependence on imports. Around 25% of all food was produced domestically before the war, with Yemen otherwise relying on imports. The figure declined to less than 20 per cent in 2017. Domestic food production is reported to have dropped even lower in 2018.

Higher prices for agricultural products such as seeds and fertilizer, fuel shortages and continuing fighting to restrict access to fishing grounds and agricultural land led to a decline in local food production below the average rainfall. Since February 2017, the cost of cooking fuel, particularly gas, has also risen sharply. Cooking fuel has at times been scarce in places near to the frontlines. This makes Yemen far more dependent on costly imports of food or humanitarian aid to survive.

No Clean water access

Every day, millions of Yemenis battle to find enough clean water for cooking and washing. The world’s worst cholera epidemic has also struck Yemen. In areas that lack adequate sanitation facilities, cholera is spread by polluted water or food and thrives. It has affected 1.3 million individuals and caused 2,800 people to die. They lack access to clean water and sanitation for 17.8 million people and are at risk of contracting cholera.

Yemen’s tremendous spike in cholera, malaria and acute diarrhoea has worsened the country’s malnutrition crisis. Yemen’s health system is also approaching a breaking point, suffering from severe fuel and medical supply shortages, which have left the nation unable to respond.

Humanitarian response to the Yemen crisis

Response from WFP

The Yemen emergency response from the WFP is our most significant emergency response anywhere in the world. In 2019, the WFP aimed to feed 12 million chronically hungry individuals per month-a 50 per cent rise in the number of individuals we served last year.

Our mission is to ensure that the life-saving support they need every month is provided to all families suffering devastating food shortages. The goal of the WFP is to steadily expand its funding to meet all 12 million targeted beneficiaries in a variety of ways.

General Food Assistance

The WFP offers monthly food rations to communities where the local economy has failed mainly because of the war. The WFP provides families with product coupons or even cash to purchase the same amount of food as included in the monthly rations if the local markets are still working. In addition to helping families meet their everyday food needs, vouchers, and cash provide the local economy with a vital boost, which is essential to place Yemen on the path to recovery.

Nutrition

To meet 3 million children under five and pregnant or nursing women in 2019, the WFP is scaling up its nutrition work. The WFP’s nutrition work is now centred on 165 districts, in addition to a malnutrition recovery programme, where we are working to reduce malnutrition for women and children. WFP is running a robust supplemental feeding programme that will provide 700,000 children under two with nutritional assistance and 300,000 pregnant or breastfeeding mothers.

But, particularly for children, the situation in Yemen remains critical. Malnutrition today will have devastating implications for Yemen’s future, as it irreversibly stunts the growth of children and the development of the brain. For decades to come, long after the war ends, this will have a damning impact on Yemen’s growth and GDP.

Meals from School

WFP is now supplying 600,000 children with a daily healthy snack through its School Meals Programme. We aimed to hit 900,000 kids per day in 2019. Not only does the school meals programme offer a critical nutrition boost for children, but it also helps keep them in school.

Conclusion

The destructive effect on food security is long-lasting, partially because it is a self-defeating cycle of hunger and conflict. Conflict increases food insecurity, and food and nutrition insecurity increase the risk of instability, crime, and war. Although conflict is by no means the only global hunger perpetrator, it is the primary catalyst. Indeed, the bottom three of this year’s GHI countries (CAR, Chad and Yemen) are all in the middle of the war, and 60% of the hungry people in the world currently live in conflict zones.

The solutions to hunger are straightforward and complex: simple are the fundamental strategies themselves, many of which are easy to take. It is more challenging to make the change happen permanently and sustainably and to find the best mix of solutions for each group.

- Climate-smart agriculture

- Responding to forced migration

- Fostering gender equality

- Reducing food waste

- Investing in disaster risk education

- Supporting hygiene and sanitation

- Controlling infestations and crop infections

- Improving food shortage system

From the solutions mentioned above to get Zero hunger, we can manifest ourselves to start with small steps like not wasting any food and gender equality in our environment.

Follow us on FACEBOOK, INSTAGRAM and TWITTER to stay connected.

Also, Read- What is Global Hunger Index? And Top 4 countries suffering worst from a Hunger crisis.